Bollywood News

“When we moved to Mumbai, Manoj Bajpayee and I paid Rs 2,000 per month in rent; that’s not possible today,” says Saurabh Shukla.

Published

2 weeks agoon

By

India.jpg)

Saurabh Shukla shared that he, along with Manoj Bajpayee, paid minimal rent in Mumbai in the 1990s, but it is not possible for a new actor to do that today.

The 1994 movie Bandit Queen, starring Shekhar Kapur, gave the Hindi film industry a new generation of performers who later relocated to Mumbai and accomplished great achievements. Manoj Bajpayee, Saurabh Shukla, Gajraj Rao, and several more were among them. According to a recent interview, Saurabh said that in the 1990s, they were not overly concerned about their financial situation or their prospects. According to Saurabh, a struggling actor nowadays cannot afford to be as laid back since the business’s economics have changed.

“I never imagined that I would start working in films,” Saurabh said in an interview with the YouTube channel Filmore India. He revealed that he had the courage to launch a career in Mumbai after working in theatre for a few years in Delhi and then with Shekhar in Bandit Queen. With aspirations of becoming a filmmaker, he relocated to the city.

“When we moved to Mumbai, Manoj Bajpayee and I paid Rs 2,000 per month in rent; that’s not possible today,” recalls veteran actor and writer Saurabh Shukla, reflecting on a bygone era that seems almost fictional to today’s generation.

Those were the days when ambition was high, pockets were light, and the city of dreams was far more forgiving. Both struggling actors at the time, Saurabh Shukla and Manoj Bajpayee arrived in Mumbai with big dreams and minimal resources. Sharing cramped spaces, eating frugally, and working odd jobs were part of the routine. But rent for Rs 2,000? In today’s Mumbai, that figure wouldn’t even get you a corner in a chawl, let alone a room with basic facilities.

Back then, even that modest sum seemed like a challenge, but it was doable—just enough to scrape by while pursuing their acting dreams. Shukla’s reflection offers a stark contrast to the current real estate market, where rental prices in even modest neighborhoods have skyrocketed. The same apartment they once rented would today demand upwards of Rs 20,000 to Rs 50,000, if not more, depending on the locality.

This change is symbolic of more than just inflation—it marks a shift in the entire cultural and economic fabric of Mumbai. Today, aspiring actors moving to Mumbai often take up shared flats, bunk beds in hostels, or pay guest arrangements that still cost a significant portion of their earnings or savings. The financial pressure is higher, competition is fiercer, and the journey to stability far more complicated.

Saurabh Shukla’s memory of those early days isn’t just about the money—it’s about the spirit of struggle, about living with little but dreaming endlessly. He and Manoj Bajpayee would discuss scripts, theatre, performances, cinema, and the idea of art over late-night tea and roadside snacks. The rent may have been low, but the cost of hard work, perseverance, and belief in oneself was as high as ever.

It’s worth noting that both these actors have gone on to become stalwarts in Indian cinema—respected not just for their acting prowess but for the integrity with which they’ve conducted their careers. For Shukla, known for his powerful performances in films like Satya, Jolly LLB, Barfi!, and Raid, and Bajpayee, the tour de force behind characters in Gangs of Wasseypur, Aligarh, and The Family Man, the humble beginnings continue to ground them even as they receive awards and accolades.

When Saurabh reminisces about those Rs 2,000 days, it’s not out of nostalgia for cheap rent but for a time when life was simple, passion was the fuel, and each small win meant the world. Mumbai has changed since then—urbanisation, migration, and economic shifts have made it one of the most expensive cities in the country. Yet, the magnetism it holds for dreamers remains unchanged. For every Manoj and Saurabh of the 90s, there are hundreds today who arrive at the city’s railway stations with a bag in hand and hope in their eyes, looking to make it big in Bollywood or beyond.

Saurabh Shukla’s anecdote is not just a tale of economic disparity over decades—it is a reminder that legends are often born in the smallest of rented rooms, with flickering lights, leaky ceilings, and unpaid electricity bills. The room they shared may not have had comforts, but it had character. It was witness to the birth of performances that would one day move millions.

It was the silent keeper of frustration, hunger, laughter, and friendship. In those cramped walls, they rehearsed dialogues, faced rejections, supported each other, and held on to the only thing they had in abundance—dreams. His story also shines a light on the housing reality for artists in urban India. While actors with film families or financial backing may have it easier, the self-made ones still go through the grind. Rent, survival jobs, daily auditions, unpaid gigs—it’s a cycle that hasn’t changed.

What has changed is the support system and awareness, to some extent. There are now more platforms, digital mediums, and training institutes. But even then, the financial struggle remains real. Saurabh’s journey alongside Manoj serves as a living testimony to what perseverance can achieve. It shows how bonds formed in struggle often last a lifetime.

Theirs wasn’t just a friendship—it was a shared fight against anonymity in a city brimming with talent. As Shukla narrates this slice from the past, one can sense a mix of pride and humility. Pride in the distance traveled, and humility because he knows what it took to get there. The tale, simple as it may sound, is layered with life lessons—about ambition, patience, sacrifice, and the will to endure.

It’s a reminder to the new generation that while the rents have gone up, and the avenues may have multiplied, the essence of ‘making it’ remains the same. It requires the same hunger, the same grit, and the same belief. Saurabh Shukla’s reflection is not just personal history—it is a window into a cultural moment of Indian cinema, where the future legends lived like ordinary men and found joy in the journey, not just the destination.

That Rs 2,000 rent, in many ways, was the foundation upon which careers were built. And though it may no longer be “possible today,” the story continues to inspire countless others chasing a similar dream in an ever-expensive city.

Saurabh Shukla recently shared a memory that might sound unbelievable to anyone living in Mumbai today. He spoke of a time when he and Manoj Bajpayee, both still unknown to the wider world, shared a modest space in the city and managed to pay just ₹2,000 a month for rent.

It’s a figure that now seems like a relic from a forgotten past, yet it was very real to them back then. The rent was small, but it came with big dreams and even bigger uncertainties. That room was more than four walls—it was a haven for two struggling artists trying to find their place in a city that seldom offers second chances.

In those days, the glamour of Mumbai was mostly out of reach. The glitz of the film industry was a distant glow that barely touched the lives of outsiders like them. They had arrived in the city not with money or connections, but with passion and relentless drive.

The room they lived in wasn’t luxurious, but it was functional. A single bed, a creaky fan, maybe a shared bathroom down the hall—but it gave them space to exist, to plan, to hope. Every rupee mattered, and splitting rent was an act of survival. One missed audition or unpaid role could upset their monthly finances.

While today’s Mumbai is dominated by high-rises and sky-high rents, the Mumbai of their time still had pockets of affordability. Old buildings, chawls, and single-room units offered shelter to migrants chasing careers. The city was not kind, but it was accessible in ways that feel impossible now. With Rs 2,000, two people could carve out a corner to breathe, to create, and to rehearse lines that would one day become iconic performances.

They weren’t surrounded by luxury or fame. They cooked their own meals, washed their clothes by hand, and shared cups of tea at roadside stalls. Their evenings were filled with conversations about theatre, cinema, and survival. They watched each other go through the highs of being shortlisted for a role, and the lows of walking out of auditions without being heard. In that rented room, ambition slept on a mattress on the floor, and hope hung like laundry on rusted wires.

No one saw them then as stars. They were just two men trying to navigate the chaos of the city. When the rent date approached, they’d count coins, delay meals, or skip transport to make up for shortfalls. There was no backup plan—only belief. They didn’t have air-conditioned studios or agents. What they had were their instincts, their raw talent, and the strength they found in each other’s company.

Today, getting a single room in Mumbai—even on the outskirts—can cost up to 10 or 20 times what they paid. And that’s without factoring in deposits, utility bills, or food. For a newcomer, especially someone with no family support, the cost of living alone can be suffocating. The ₹2,000 Shukla talks about wasn’t just affordable—it was liberating. It allowed them to dream freely, without being crushed under financial stress.

But the value of that room wasn’t just in its price. It was in what it allowed them to become. It was the place where lines were memorized, failures were discussed, and doubts were overcome. It saw laughter after rejection, quiet confidence before performances, and hours of discussion about what it means to be an artist. It stood silently while they built their identities brick by brick.

Saurabh Shukla’s path from that room to award-winning roles has been paved with resilience. He has played everything from comic relief to intense supporting characters, and his presence in Indian cinema is now legendary. Manoj Bajpayee, too, has carved out a space that few can match, with performances rooted in sincerity and skill. And it all began in a humble room where two actors once argued about cinema late into the night, dreaming about roles they didn’t yet have the power to claim.

The apartment didn’t come with conveniences. There were power cuts. The walls may have been stained. The floor may have been hard. But none of that mattered. What mattered was that they had a place to return to at night—a place to rest their heads after long, disappointing days. That sense of shelter is something few outsiders to Mumbai can afford now without hefty compromises.

There’s a quiet dignity in how Shukla talks about that phase. Not as something tragic, but something formative. Struggles didn’t break them—they sharpened them. They learned how to work with little, to make do with what they had, to turn setbacks into stories. And above all, they learned how to stay the course.

Mumbai has changed drastically since those days. The skyline is taller, the roads more congested, the rents unforgiving. But what hasn’t changed is the soul of the city—a place that, even when brutal, gives space to those who persist. Thousands still come here each year hoping to make it in cinema. They take jobs as assistants, work in call centers, or become extras just to stay close to the dream. And while the costs have gone up, the emotion remains the same.

Shukla’s memory is a reminder of the invisible history behind visible success. We often see the award speeches, the red carpets, and the headlines. But behind every recognition is a story like this—of two friends splitting Rs 2,000 rent, choosing survival over comfort, and believing in themselves when no one else did. That kind of faith can’t be bought, only earned through time.

Even if that exact room still exists somewhere in Mumbai, it won’t be the same. The city doesn’t pause. What was once a refuge for unknowns might now be listed as a premium studio apartment online. But for Saurabh Shukla and Manoj Bajpayee, that room lives on in memory—as the backdrop to a chapter that defined their careers and their friendship.

It’s easy to talk about how hard things are today. But looking back at their story, we’re reminded that while costs may rise, what really makes the difference is commitment, courage, and the willingness to keep going. That ₹2,000 room may be long gone, but its legacy is stitched into the fabric of Indian cinema.

- Group Media Publication

- Construction, Infrastructure and Mining

- General News Platforms – IHTLive.com

- Entertainment News Platforms – https://anyflix.in/

You may like

-

.jpg)

.jpg)

Sufi Motiwala describes Karan Kundera’s expulsión injusta en The Traitors, asegura haber mantenido un ‘no vínculo’ con Uorfi; anticipa un sorpresivo giro: ‘Un competidor recibe un funeral’

-

.jpg)

.jpg)

Kesari Chapter 2: Accidentally, Akshay Kumar’s drama in a courtroom reveals Bollywood’s manejo de sexual misconduct.

-

.jpg)

.jpg)

They said Vidhu Vinod Chopra bribed me with Rs 8 crore to not make OMG’: Director Umesh Shukla opens up on PK comparisons

-

.jpg)

.jpg)

Stranded in Israel amid airstrikes, Caitlyn Jenner sips wine in bomb shelter and says, ‘Pray for us’

-

.jpg)

.jpg)

After three years, Alia Bhatt and Ranbir Kapoor’s six-story Bandra home, valued at Rs 250 crore, is ready, and fans exclaim, “Gate nahi hai.” Observe

-

Paresh Rawal responds to a fan who refers to him as the “hero” of Hera Pheri 3 and asks him to reevaluate his departure: “There are three heroes.”

Celebrity Interviews

They said Vidhu Vinod Chopra bribed me with Rs 8 crore to not make OMG’: Director Umesh Shukla opens up on PK comparisons

Published

6 days agoon

June 14, 2025By

India.jpg)

In a surprising revelation that has reignited a long-standing debate in Bollywood, director Umesh Shukla has addressed the whispers and controversies surrounding his 2012 satirical film OMG: Oh My God! and the later 2014 film PK, directed by Rajkumar Hirani. In a candid interview, Shukla broke his silence on allegations that producer Vidhu Vinod Chopra offered him a bribe of Rs 8 crore to shelve OMG, a claim that reflects the intense behind-the-scenes politics in the Hindi film industry.

Umesh Shukla, known for his directorial boldness in tackling religious orthodoxy and blind faith through humor and satire, has often been asked about the uncanny thematic similarities between OMG and PK. Both films feature protagonists who question the institutionalization of religion and challenge blind belief systems, although their narrative styles and presentations differ significantly.

According to Shukla, the rumors about a bribe were not just baseless but deeply hurtful. He stated that during the production of OMG, many industry insiders warned him against treading on controversial themes. Some even suggested that powerful people in Bollywood were trying to stall his project by offering financial incentives, but he remained undeterred.

“I had heard that Vidhu Vinod Chopra gave me Rs 8 crore to not make OMG, but that’s completely false,” Shukla asserted, expressing disbelief at how easily such narratives were accepted by the public without verification. He emphasized that the story of OMG was deeply personal to him and born out of his desire to provoke thought through cinema.

The controversy took a sharper turn when PK, starring Aamir Khan, was released just two years after OMG and explored nearly identical themes of questioning religious dogma. While PK took a more fantastical route, introducing an alien protagonist who struggles to understand Earth’s religious customs, OMG kept its storytelling grounded in realism with Paresh Rawal’s character, a shopkeeper who sues God after his shop is destroyed in an earthquake.

Fans and critics quickly drew parallels between the two films, with many suggesting that PK borrowed heavily from OMG. The similarity in central themes and the treatment of religious satire led to accusations of idea theft, sparking a debate about originality and influence in Bollywood.

Shukla’s recent comments have rekindled interest in the timeline of both films. He pointed out that OMG was based on a Gujarati play titled Kanji Virudh Kanji, which itself had been staged long before PK entered production. The play, and by extension OMG, was already well-known among theater circles, making the claims of copying absurd, according to him.

Adding to the complexity, both films featured strong performances and starred powerhouse actors—Paresh Rawal and Akshay Kumar in OMG, and Aamir Khan and Anushka Sharma in PK. The commercial success of both films showed that audiences were hungry for content that questioned norms and dared to speak against blind faith.

Shukla emphasized that no amount of money could have made him abandon a story he believed in so deeply. “You cannot put a price on conviction,” he said, adding that he faced immense challenges during the making of OMG, including threats from fringe groups and legal notices that attempted to ban the film.

The controversy also highlights the power dynamics in Bollywood. While Shukla was working with limited resources and a modest budget, PK enjoyed a massive production scale, international locations, and a superstar at its helm. This disparity made many believe that PK overshadowed OMG, although both films carved their own niches.

In recalling the production journey of OMG, Umesh Shukla shared that it was never a film meant for controversy—it was created to start conversations. He stressed that the core objective was to urge people to think critically about the rituals and traditions they follow blindly, rather than mocking any particular religion or belief system. His conviction was that cinema could be an effective medium to challenge the status quo without inciting hate.

Shukla mentioned that OMG was initially seen as a risky project. Studios were hesitant to back it due to its sensitive subject matter. “Many people told me it wouldn’t get released or would be banned outright,” he said. However, once Akshay Kumar came on board as both producer and actor, the film gained momentum and credibility. Akshay’s support gave the project the push it needed to reach audiences.

The director also explained how important casting was in shaping OMG. Paresh Rawal, who had already portrayed the character Kanji on stage, brought authenticity and depth to the screen version. His performance was lauded for its balance of sarcasm, sincerity, and emotional vulnerability. Shukla credits Rawal’s theatrical experience as the key to humanizing the film’s bold message.

When asked directly about PK, Shukla was diplomatic but firm. He said he has nothing against the film or its makers, but it’s undeniable that the similarities between the two were “too convenient to ignore.” While he avoided accusing anyone outright of plagiarism, he maintained that the creative overlap left him and others with a sense of déjà vu that couldn’t be dismissed.

Another aspect of the conversation was the timeline. Shukla emphasized that OMG had already been conceptualized, written, and nearly completed by the time he heard about PK being in development. This timeline discrepancy, he believes, is why many suspect that the latter may have drawn inspiration from his film. He finds it unfortunate that people in the industry rarely speak up about such matters due to fear of backlash.

Despite the challenges and comparisons, Shukla takes pride in the cultural impact of OMG. He recalled receiving messages from audiences across India, including small towns and conservative regions, thanking him for making a film that gave voice to their doubts and questions. For him, that validation mattered more than box office numbers or critical acclaim.

He also revealed that OMG faced legal hurdles and community protests before and after its release. Certain religious groups filed cases alleging the film was blasphemous. “There were screenings with police protection,” he said. “We had to go to court to defend our right to express ourselves artistically.” He believes those experiences made him stronger as a filmmaker.

Interestingly, Shukla believes that the controversy and comparisons between OMG and PK opened the floodgates for more films to explore philosophical and religious themes without fear. He noted that films like Article 15, Lipstick Under My Burkha, and The Kashmir Files may not have emerged so boldly if earlier projects hadn’t tested the waters.

He further clarified that the rumors about the Rs 8 crore bribe had originated from online gossip and unverified sources, which were then picked up by tabloids. “There’s no truth to it, but once a lie spreads, it’s hard to catch up with it,” he said. “Sometimes I think people want controversy more than the truth.” His tone was not bitter—rather, it carried the resignation of someone who has seen the industry from the inside.

In the years since OMG, Shukla has continued to work on socially relevant content. He directed 102 Not Out, a heartwarming story about aging and father-son relationships, and has continued exploring themes that challenge societal norms. But he admits that OMG remains closest to his heart, both for the message it carried and the battle it took to bring it to the screen.

- Group Media Publication

- Construction, Infrastructure and Mining

- General News Platforms – IHTLive.com

- Entertainment News Platforms – https://anyflix.in/

.jpg)

Sufi Motiwala describes Karan Kundera’s expulsión injusta en The Traitors, asegura haber mantenido un ‘no vínculo’ con Uorfi; anticipa un sorpresivo giro: ‘Un competidor recibe un funeral’

.jpg)

Kesari Chapter 2: Accidentally, Akshay Kumar’s drama in a courtroom reveals Bollywood’s manejo de sexual misconduct.

.jpg)

They said Vidhu Vinod Chopra bribed me with Rs 8 crore to not make OMG’: Director Umesh Shukla opens up on PK comparisons

.jpg)

Stranded in Israel amid airstrikes, Caitlyn Jenner sips wine in bomb shelter and says, ‘Pray for us’

.jpg)

After three years, Alia Bhatt and Ranbir Kapoor’s six-story Bandra home, valued at Rs 250 crore, is ready, and fans exclaim, “Gate nahi hai.” Observe

Paresh Rawal responds to a fan who refers to him as the “hero” of Hera Pheri 3 and asks him to reevaluate his departure: “There are three heroes.”

.jpg)

Housefull 5 Day 3 Box Office Collection: ₹91 Cr Milestone for Akshay Kumar

.png)

Four years after her divorce, did Samantha Ruth Prabhu get rid of her tattoo with the Naga Chaitanya link? Supporters are persuaded

Thug Life Movie Review & Release Live Updates: Kamal Haasan’s Bold New Venture – Is it the Hit We Expected?

%20(2).jpg)

Kareena Kapoor reveals her new schedule; says she has dinner at 6pm, lights out at 9:30 pm: ‘Saif, the kids and me, we’re all cooking together’

According to Urvashi Rautela, Leonardo DiCaprio referred to her as the Queen of Cannes; online users refer to him as the “first Hollywood star to

First impression of a good boy: Don’t let “Pouty” Park Bo Gum deceive you; he’s throwing punches of his career.

Thug Life Movie Review & Release Live Updates: Kamal Haasan’s Bold New Venture – Is it the Hit We Expected?

.png)

Four years after her divorce, did Samantha Ruth Prabhu get rid of her tattoo with the Naga Chaitanya link? Supporters are persuaded

Gauahar Khan criticises Suniel Shetty’s C-section remark, reveals she suffered a miscarriage: ‘For a male celebrity who didn’t go through pregnancy…’

%20(1).jpg)

Actor Hailee Steinfeld marries Buffalo Bills quarterback Josh Allen in dreamy ceremony

.jpg)

Stranded in Israel amid airstrikes, Caitlyn Jenner sips wine in bomb shelter and says, ‘Pray for us’

.jpg)

“I haven’t seen a man with such great kindness,” Zeeshan Ayyub remembers when Shah Rukh Khan handed him his own sweater.

Thug Life Movie Review & Release Live Updates: Kamal Haasan’s Bold New Venture – Is it the Hit We Expected?

The anime Tokyo Revengers is back with a sequel: view the promotional trailer

Deadpool and Wolverine might shatter box office records, which would be unprecedented for an R-rated film.

Review of Bridgerton Season 3 Part 2: Nicola Coughlan excels in the most intricate and captivating season to date

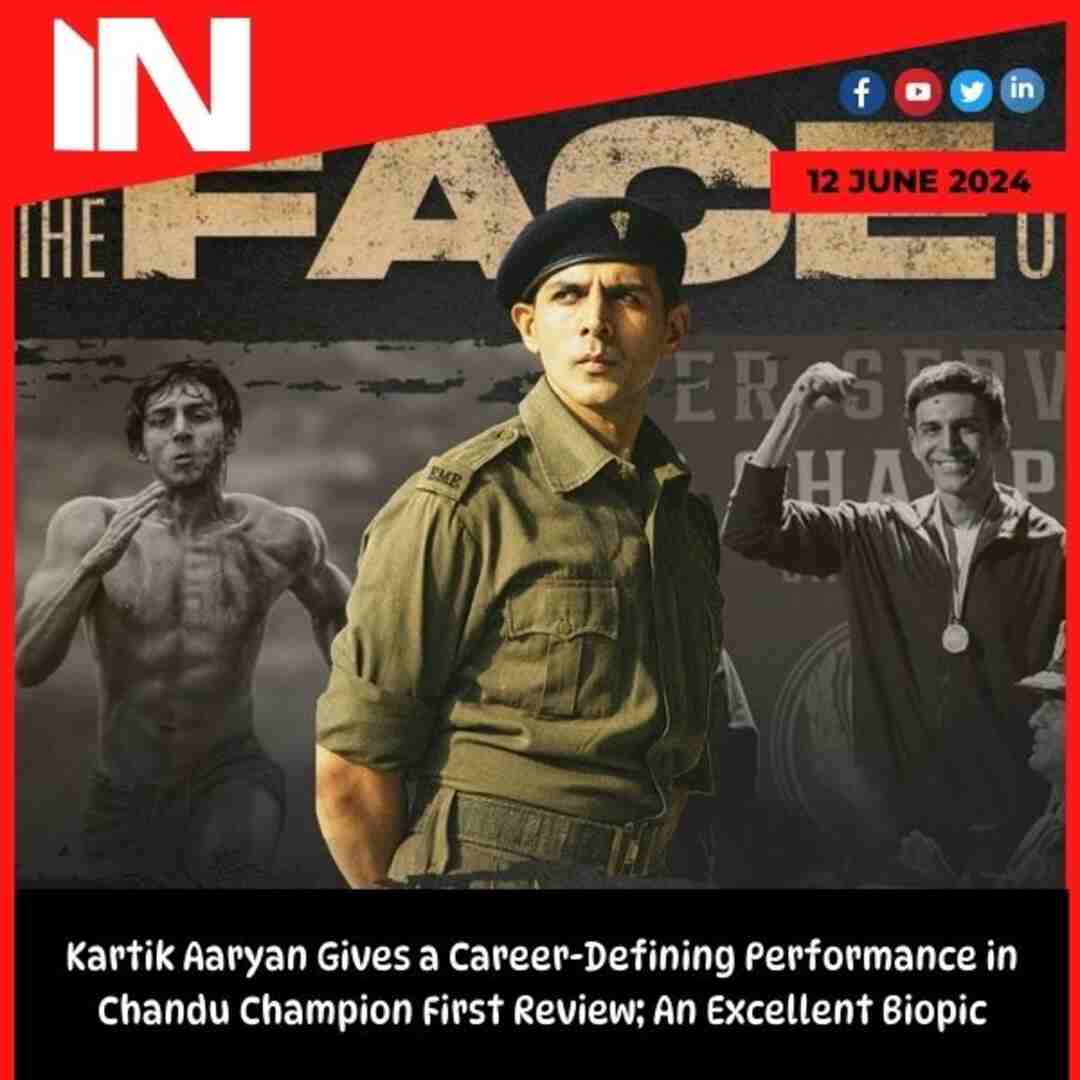

Kartik Aaryan Gives a Career-Defining Performance in Chandu Champion First Review; An Excellent Biopic

Watch the trailer for Kota Factory 3 here. Fans of Jeetu Bhaiya say they’re not ready for it to end.

Kartik Aaryan on overcoming the label of “outsider”: It will remain with me, and that is alright with me.

When Does Vishwak Sen’s Film Gangs of Godavari OTT Come Out? What Platform Does It Come Out On?

Review of Gullak 4: A lovely, sentimental, and somewhat mature reunion of the Mishra family

Trending

-

Ranbir Kapoor2 months ago

Ranbir Kapoor2 months agoRanbir Kapoor and Alia Bhatt inspect their new dream home in Mumbai days after anniversary

-

Mahakumbh2 months ago

Mahakumbh2 months agoMahakumbh viral girl Monalisa looks unrecognisable after glamorous transformation in new videos: Watch

-

American Dream2 months ago

American Dream2 months agoThe new American dream’: Meet the US expat who built a $23M food business in India

-

.jpg)

.jpg) Bollywood2 months ago

Bollywood2 months agoSiddharth Malhotra carries pregnant wife Kiara Advani’s bag in unseen pic from New York ahead of Met Gala 2025

-

Sunny Leone2 months ago

Sunny Leone2 months agoSunny Leone’s fitness secrets for toned body at 43: Vegetarian diet to different menu every day for lunch and dinner

-

SSC Exam Calendar 20251 month ago

SSC Exam Calendar 20251 month agoSSC Exam Calendar 2025 revised, check CGL, CHSL, SI in Delhi Police, MTS, JE and other exam dates here

-

Ajith Kumar2 months ago

Ajith Kumar2 months agoAjith Kumar says he could be ‘forced into retirement’, calls himself an ‘accidental actor

-

YouTube2 months ago

YouTube2 months agoYouTube marks 20th anniversary by launching new useful features What’s new